As Shutdowns Shake the World, Migrants and the Homeless Bear the Brunt

By: Jonathan Stormer Pezzi

A migrant sells merchandise on the beach. Photo by Marco Pomella

New York — As the world stoops under the weight of COVID-19, certain populations are bearing the brunt of the shutdowns.

On the streets of Washington D.C., the closing of aid organizations and public shelters has devastated the homeless population. Nonetheless, many non-profits are still working to provide the bare necessities for those in need.

“There is an overflow of homeless on the streets now, who are using the boarded up shops as shelters. It looks to be an overflow of homeless travelers as well, who are coming into the city looking for money since many are being pushed out of low income jobs and having to live on the streets to make ends meet,” says Wyatt Knight, a co-founder of Change4ChangeDC, an organization created to assist the homeless population in Washington DC.

Knight also mentions that many of the homeless are too afraid to sleep in shelters due to the close quarters.

Although Change4ChangeDC and many other non-profits have been forced to refrain from extensive in-person assistance, they have begun to adapt.

Photo via Change4ChangeDC’s Instagram.

“We are being thoughtful that the biggest priority right now for all of us is staying inside and doing our part,” Knight went on. He did note that a few times a week he and other members of Change4Change would venture out to donate food, clothes, and gear to the homeless community in their neighborhood, of course taking all the necessary precautions.

“We feel times like these are the exact reason why C4C exists. So we are doing the best we can during this unique time.”

Across the Atlantic, the European nation hit hardest by the virus, Italy, is struggling to care for an enormous migrant population.

Many government offices and non-governmental organizations have closed their doors; doors that otherwise would be assisting migrants in their settlement process.

“For recent migrants, the situation is very difficult. There are some forms of support provided mainly by associations and charities, but at this time it's hard to know if volunteers (can) keep on helping them,” says Chiara Damiani, a coordinator for the Amir Project, an initiative in Florence that trains migrants as tour guides for the city’s exalted art museums.

Normally, if these migrants are recognized as refugees they have the right to services provided by the Protection System for Refugees and Asylum Seekers (SPRAR), which administers professional training and Italian language courses. Those services have now been suspended.

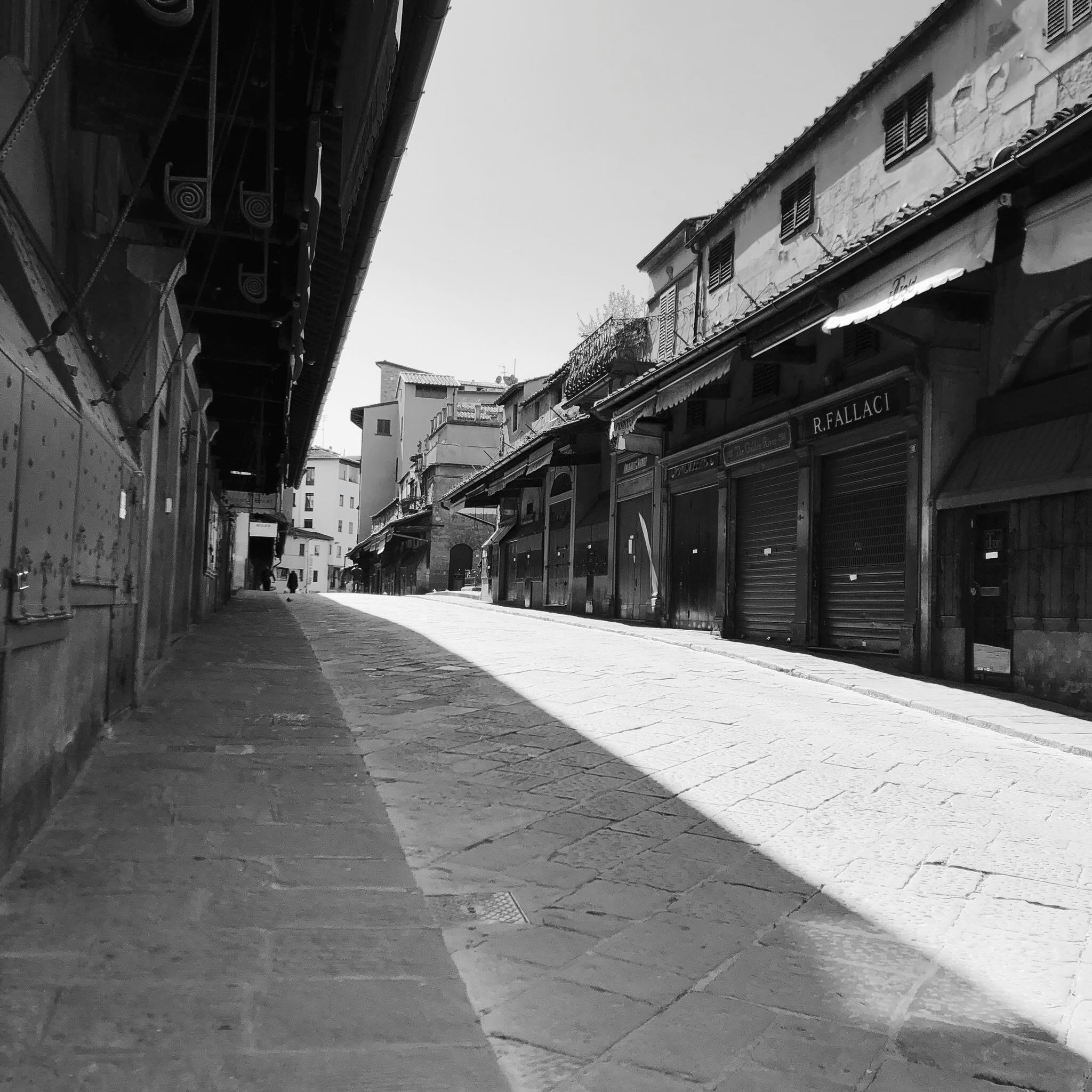

Photos of the barren streets of Florence, a city usually teeming with visitors. Photos by Michelle Ayer

As conditions in camps and temporary shelters are prone to the spreading of disease, institutions like the Catholic Church have lent a helping hand. Father Massimo Biancalani in Pistoia began housing undocumented immigrants, allowing them to sleep in his church. Unfortunately, this temporary fix was not seen as adequate. Health officials are requesting the migrants be transferred to facilities with better access to health care.

"Before the quarantine I used to work but it was not a contract. I work by day and have my pay for one week," a migrant told one non-profit. He added that he now has nothing to pay rent.

Another migrant in Salerno, Italy says, "My (asylum) case was rejected for (the) second time on February and (I) am now homeless. In early March I went to my center to stay there because of the spreading of coronavirus and I was thrown outside. Now I sleep in an uncompleted building and I have to hide myself to walk at least 15 minutes to the camp and eat."

These tribulations of migrants are also occurring in areas of the world where the virus is not as prominent. Many Nepali workers previously living abroad tried to return home after the virus affected their jobs, only to be stopped at the border. Now, dozens of Nepali workers are stranded at the junction, sleeping in tents until they are permitted to cross. There is no clear timeline for when that might be. As many as 500 Nepali workers are stranded at the Indian-Nepal border.

In the capital of Nepal, Kathmandu, the situation for the low-income population is bleak as well.

“We have no jobs since the lockdown began, and it’s extending every week. We are staying at home, running out of food and money. We don’t have any other friends or support systems like in the village. The situation is very uncertain and it’s difficult for us to survive in Kathmandu. Therefore, we are obliged to walk home on foot even though the journey is long and difficult. We are in a group of 10 friends going in the same direction. It will take at least 4 days to reach home. But we will slowly make our way home because there’s no option left for us,” says Rohinda Manda, a migrant construction worker, in an interview with Record Nepal, a digital publication based in Kathmandu.

As the poorest countries are hit harder by the virus, these problems will likely exacerbate. To help developing nations, the World Bank has pledged $12 billion in emergency aid and the United Nations has requested an additional $2 billion from member states. Some see the stories of migrants and the homeless in the West as a grim foreshadowing for what is to come, as countries with fewer resources are struck by a new wave of the virus.