Martin County, Kentucky’s Water Crisis Isn’t Over. But It Has Changed.

By: Jonathan Pezzi / @jonathan_pezzi

New York — In Martin County, Kentucky a rusty, brownish liquid often shoots out of sinks in short bursts, then weakly drips down into the drain.

Residents are forced to buy bottled water in bulk — brushing their teeth, cleaning their dishes, and drinking from the store bought water. Some simply collect runoff from a rocky promontory, harnessing what they need in gallon milk jugs.

Access to consistent, clean drinking water has plagued Martin County for years. Only recently has it started to receive more coverage.

A series of articles by major media outlets in 2018 helped bring this issue to nation-wide attention. But it was the efforts of country music star Tyler Childers, who visited the county following a multi-day stint without water, that helped galvanized many Kentuckians to call for change.

At the time, the water in Martin County was virtually undrinkable. Residents reported discoloration, potentially harmful substances, and water pressure so weak that some could only garner drops from their faucet.

Two years later, certain aspects have relatively improved—but after a new roadblock emerged, reliable water services are still not a reality for many. Martin County now has one of the highest water prices in the state.

Numerous factors have made bills unaffordable for the county’s residents.

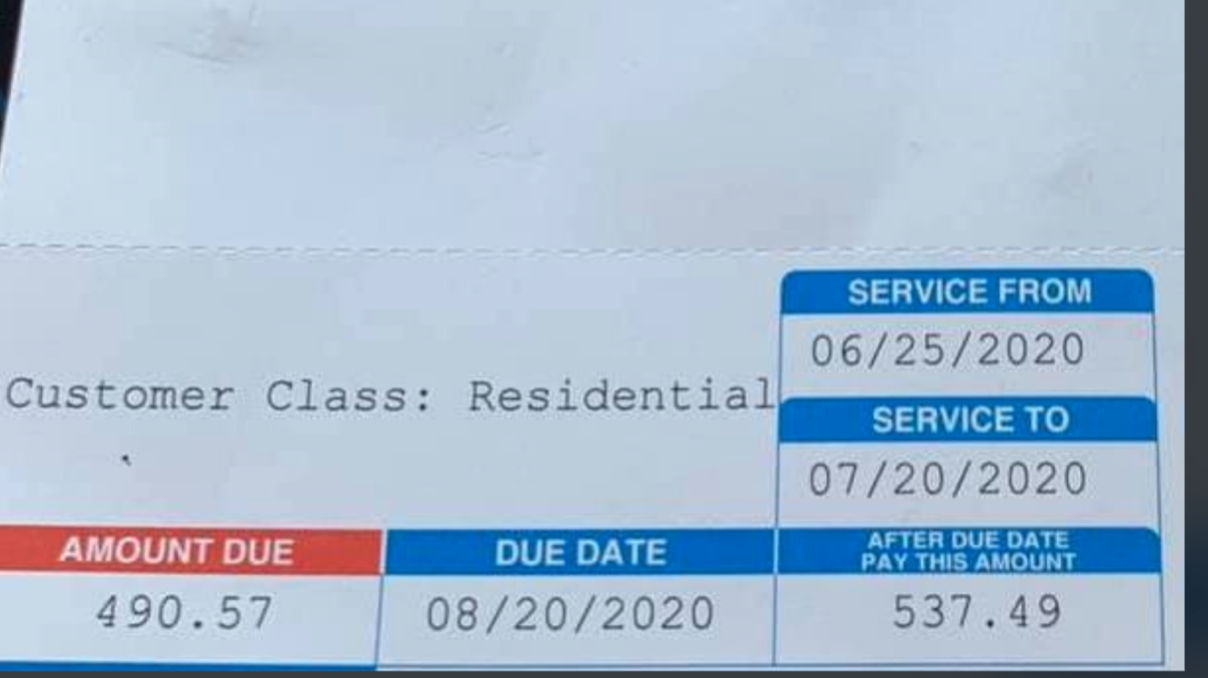

In addition to a new $3.16 surcharge, pictures of Martin County residents’ water bills have ambled around social media, illustrating bafflingly high charges for residents living in modest households and on low-incomes.

This resident was charged $490 for their monthly water bill. The average nationwide is $79.

Contrary to common perception, these bills are not simply from rate increases. A combination of human and software errors are mostly responsible for the gross overcharges.

Some households’ bills show they used 50,000+ gallons of water, over four times the nation’s average. Considering the vast majority of the county does not use their utility’s water for drinking or cooking, this number is very unlikely.

These numerical mistakes could be partially attributed to the water district’s leakage problem. Studies have found that approximately 70% of Martin County’s water is lost through leaking pipes.

Accounting errors are also occasional explanations for these high bills. But on average, residents are paying more for their water, even without the mistakes.

For decades, a tax on coal mining activity subsidized utility costs for residents in the county, artificially lowering people’s monthly bills. However, as coal employment and production has plummeted in the last thirty years, the funds for these subsidies have dried up. (The income from this coal severance tax fell 81% from 2012 to 2018.)

Residents are now bearing the full cost.

Unfortunately, these price increases may push some residents into financial oblivion. Martin County is one of the poorest counties in one of the poorest states in America, with a poverty rate hovering around 30%—nearly triple the national average. The median household in Martin makes just $29,239.

The U.S. News and World Report ranked Martin as the worst-performing white-majority county in the nation. The report accounted for a number of health and economic factors, including job availability, prevalence of various diseases, smoking rates, housing affordability, and air and water quality.

However, even if residents could afford the water, there is no telling whether they would start to drink it. Decades of problems have sown distrust among Martin County’s population.

A Short History of Distrust

Inez, Martin’s county seat, first built their water treatment plant in 1968. Originally built for 600 people, the facility now supports around 3,500.

For the following decades, the water district’s relationship with its customers was mostly normal, though underinvestment in the district’s infrastructure did draw concern.

That relationship changed on October 11th of 2000.

One night as the county slept, 306 million gallons of toxic coal slurry, a type of coal waste, broke through its containment reservoir into an abandoned mine just below the dangerous sludge.

The waste, brimming with arsenic and mercury, soon escaped the mine. The black spill flowed directly into two county streams, Goldwater Creek and Wolf Creek. These two tributaries empty into the Tug Fork River, the source for the county’s drinking water.

Shortly after the spill, the coal companies responsible and the Environmental Protection Agency told Martin County residents their drinking water was safe. They claimed the water filtration plant was able to remove the harmful contaminants.

However, an originally undisclosed water plant inspection report revealed that the water plant’s filters were not washed properly and some of the filter control valves were not fully functional.

When customers found this out, trust between residents and their water suppliers started to deteriorate.

A later investigation in 2002 by the state government in Frankfort found forty-three areas that needed addressing within the water district.

Four years later, when the state government returned to the county for further inspection, they found most of their recommendations were not implemented. They followed up by making further recommendations, bringing the total to seventy-eight areas for improvement.

Ten years after their follow up in 2006, the state discovered that many of their previous seventy-eight recommendations were again, not implemented.

After nearly two decades of regulatory avoidance, people started seeing brown and cloudy water coming out of their faucets and showers. For one stretch of time in 2018, the water completely shut off for thousands.

Now, only 12% of the county uses water from the tap.

The Crisis Today

A water-contamination report released in 2020 found that Martin County was in compliance with EPA regulations. However, there is more to the story.

EPA standards allow drinking water to exceed the maximum level of certain byproducts in individual samples, as long as the average of the samples does not exceed that level.

The report found that 29% of houses studied had above maximum levels of trihalomethanes, a disinfection byproduct that can cause several health problems, including cancer. 10% of houses studied had water containing another disinfection byproduct (HAA5) above the maximum levels. Because the county-wide levels of these substances did not exceed EPA requirements, the water district can write it off as a success.

According to Dr. Jason Unrine, an environmental toxicologist and chemist at the University of Kentucky, concentrations of these byproducts found in the report are similar to those in studies that showed increases in bladder cancer and certain types of birth defects.

An especially valuable insight taken from this report is survey responses from Martin County households.

Despite the improvements and meeting the EPA guidelines, 67% of respondents said they had cloudy water and excessive bubbles. 66% said their water occasionally had a bad odor. Nearly a quarter said the water they used had irritated or burned their skin, while over half say their water was discolored, usually after outages.

Though residents said these water problems are only occasional, discoloration and bad odor while still meeting EPA regulations concerns many onlookers.

Since the water crisis made headlines, there have been some changes in the district.

The district has received several grants totaling $5 million. In Sept 2019, then-Governor Matt Bevin announced Martin County would also receive $7.23 million in federal funding, though critics claim not enough money was actually allocated to water-infrastructure improvements.

This aid has helped, though it is slightly short of the estimates required for a full renovation, which is between $13 and $15 million.

New management has come to the county as well. Alliance Water Resources began to manage the county’s water and sewer operations in January. Many hoped the expertise and resources brought by the new company would alleviate the county’s struggles, but as billing problems persist, these hopes proved short-lived.

Front and western side of the Martin County Government Center, located on Main Street (Kentucky Route 40) in central Inez, Kentucky, United States. It was built in 2016.

Granted, the local management for the district has tried to help, but officials claim the community mistrust made it even harder to fix the problems.

In the past, the general distrust pushed people to bypass calling the facility when there was something wrong, instead contacting the local paper or community action group. This created more paperwork for the water district, elongating the process to find a resolution.

Though this does likely still happen, the local water advocacy group, Martin County Water Warriors, encourages its members to call the utility first whenever a problem arises.

The stubborn issues of engineering and distrust will take years to address. Despite the management shifts and millions invested for improvement, over-billing and consistency are still major problems. Just this August, a main water line broke, leaving part of the county without water. Unfortunately, the residents of Martin County and its water district are in for a long-haul.