Migrant Workers Cannot Survive Much Longer

By: James Marriott

Original Photo: Alex Sergeev, wikimedia.org

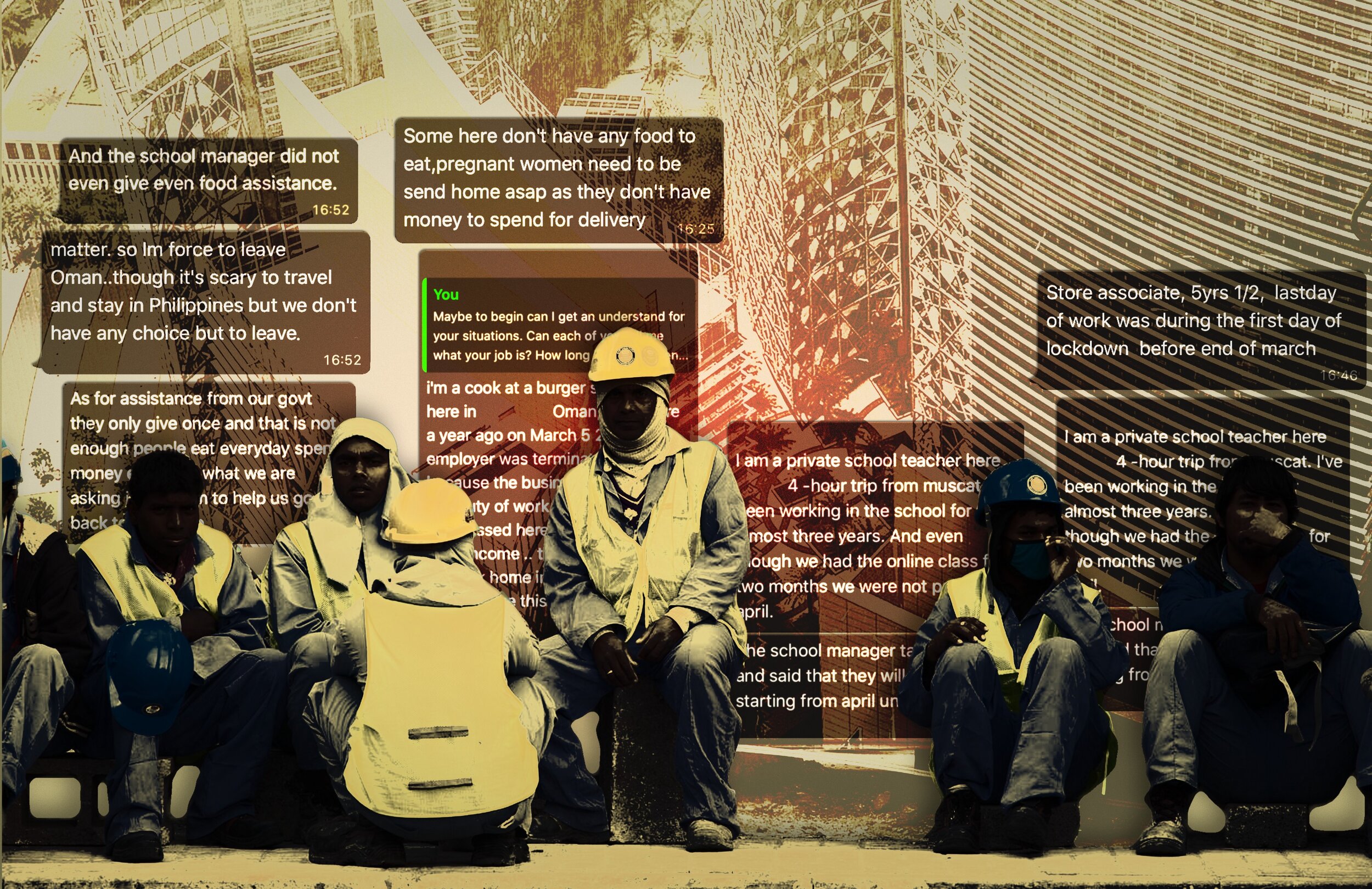

London — An irony too cruel to consider for long is the treatment of the poorest in the world by the richest in the world. In the Arabian Gulf, some of the worlds per-capita wealthiest states are disposing of the vulnerable and impoverished as the economy struggles. The image is well known: Dubai skyscrapers built by modern slave labour imported from South Asia; luxurious homes kept in check by Filipino housemaids. But whatever old paternalistic pretences that once was offered to justify this exploitation has disappeared. Economic recession is either forcefully throwing workers out of jobs or letting them flounder in their lack of stability. What was once an injustice is on the verge of a humanitarian crisis.

Migrant workers have committed suicide in shelters run by their embassy in the Middle East, and when quarantined back home. Unfortunately, there is nothing unique in this with suicides recorded in Kuwait and Bahrain (see also here). Authorities report the causes as ‘mysterious’, and given information regarding human rights is notoriously difficult to gather, one is left to speculate on their reasons. But the instability and suffering many migrant workers endure may help partly explain these ‘mysterious’ actions.

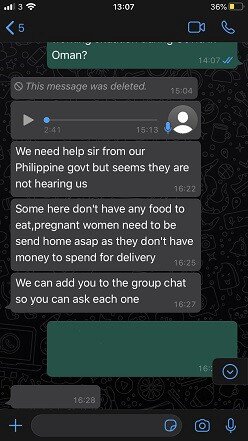

Back in June, I got in contact with a group of migrant workers in Oman. They all worked in different fields; sales associates, private school teachers, cooks, drivers etc. (I was unable to connect with someone from the construction industry). Despite these differences, they all had a similar experience. They were all either fired, not paid or about to be let go legally or illegally.

For months they had to scrape by with little to no money, relying on their embassy’s handouts or the generosity of friends still in employment. One person lived off of instant noodles and considered the ability to eat meat a treat. Some women were pregnant, and due for delivery soon, with no prospect of being able to afford the healthcare charges related to giving birth. Because of this worsening situation they wanted to return home.

But, the airport was closed, they had no money to buy a ticket, and if they did the embassy’s were struggling to negotiate an emergency flight to repatriate some of their citizens. They were simply asked to wait. As of now, embassies have begun organizing flights from Oman to various countries which the migrant workforce comes from. Citizens apply in droves and the embassy picks a select few who can fly on the limited flights. Prices for flights go up to 295 Omani rials ($765 or £610) which between one and two months income. This is income usually designated to support a family outside of Oman. And it’s here that the injustice begins to cut another way.

A look at the responses to the Facebook page of the Indian Embassy in Oman shows that migrant workers who are currently in India want desperately to come back and work in Oman. With no income for four months, people in India who have residents cards for Oman are pleading for flights so they can work and support their family. As the cruel logic goes, unjust and exploitative work is better than no work at all.

Why then is this happening? And why is it happening in the world’s wealthiest countries? Like many crises it is partly a product of unintended consequences. Even those who use this modern form of slave labour do so never envision this much instability and suffering. (Giving the Devil as much due as I can here). Now with migrant workers having no protections, the economic effects of Covid-19 are hitting them disproportionately. Not only are they at greater risk of contracting the virus, but their livelihoods are forever at the mercy of whim. The Kafala system is to blame and understanding it can help explain the humanitarian situation that is nascent.

The ‘Kafala’ System

The Kafala system allows workers from countries in the global south to come to GCC states (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, Bahrain) and work in labour-intensive and low-paid sectors. They are tied to a sponsor, who is a citizen of the country, through a work visa. Exempt from basic human, civil, and political rights migrant workers are often forced to do menial labour in unsafe conditions with the constant threat of deportation and abuse. While this is fairly common knowledge of the region recent scholarship has shown how imbricated it is within the political economies and societies of the region.

Being described as modern-day slavery, the Kafala system includes the racist implication of the term. Across the Arabian Gulf, there is a long history of slavery, the most analogues to the Western slave trade coming from the Omani Empire in East Africa. Slaves were also taken from other parts of Africa as well as Baluchistan in the south of modern-day Iran and Pakistan. This slave trade was built on violent expansion and the theft of people from their homeland. To this day racism is directed to those descendants from slave-trading regions, as well as those who migrant from them today.

Modern scholarship has refocused the discussion on the Kafala system to see how migrant labour is embedded in all aspects of society, economy, and politics. Matthew S. Hopper’s book on the East African slave trade found a crucial relationship between the Industrial Revolution globalization and the perpetuation of the slave trade. Today, Adam Hanieh writes about the similarly vital relationship between Gulf capital and the exploitation of migrant labour.

Burj Dubai Construction Workers, Source: Imre Solt, wikimedia.org

During the 1970s migrant labour was not restricted to the countries in the global south it is today. Especially because of the Israel-Palestine conflict there was a growing population of Arab migrant workers travelling to the Gulf. Migrants from Egypt, Lebanon, and Jordan brought with them the risk of importing Arab political movements so Gulf economies shifted in the 1980s to South Asia and East Africa for workers.

It was central to this process that a labouring population be depoliticized during the process of state formation. Oil-rich states bought the legitimacy of the populations through state subsidies, free healthcare, and free education while also importing a population legally and institutionally excluded from these benefits. A population devoid of any rights and stripped of a political voice to demand them. This not only creates the foundation for the Gulf states but, as Adam Hanieh explains, also helps them survive financial crises:

At times of economic turmoil, the ever-temporary nature of migrant work has been utilised as a means of effecting a spatial displacement of crisis — shifting the burden of globally induced problems on to labour-sending countries.

When the 2008–2009 financial crisis hit the Gulf, the monarchies could insulate their economies by reducing hiring and deporting migrant workers back to their home country. And so now that Covid-19 is putting the Gulf economies at risk the migrant workers are left to struggle to survive the dual-threat of viral infection and economic ruin.

The Gulf’s Economic Downturn

The lockdowns and economic standstill that has ossified the global economy has not missed out the Gulf. Oil-rich and migrant-dependent as they are, drops in the global demand for oil, years of deficit budgetary policy, and high public debt is putting a strain on the GCC states’ economies. The IMF has already predicted a 7% contraction in the Gulf economies, doubling down on a previous estimate of 3%.

Saudi Arabia is at risk of ‘domestic discontent’ as it tries to offset losses in the oil sector. In may it announced the tripling of VAT rates, preparing the country for an austerity regime in 2020. To cope with this economic reality other GCC states have begun firing employees. In Bahrain major corporations in the petroleum, aviation, and media sectors have had to cut jobs. Kuwait has begun relying on debt to survive the low oil prices, but similar problems of state budget and deficit spending await it at the end of 2020. And Oman has approached the GCC for financial aid as it is reportedly the least fiscally secure in the GCC to deal with economic instability.

These abstract numbers have begun to show real life examples on the ground. Taking Oman again as an example protests have been staged following mass firings of Omanis from large companies. In a country in which rarely has protests, and when they do cracks down on them and journalists who cover them, recent demonstrations show the severity of economic problems.

Translation: “Today/ Sunday 12–07–2020. Employees dismissed from the Eastern Sohar Iron Products Company gathered in front of a building of the Ministry of Manpower in Muscat, demanding jobs after they were stranded after useless promises from the Ministry of Manpower.

Translation: “As is common, a protest of Omani citizens gathered in front of the Hamdan Trading Company in Muscat who were arbitrarily dismissed from their jobs today. Monday, July 6, 2020.”

Translation: “In the shadow of the Carona pandemic, the world’s economy is exposed to great harm that results in the bankruptcy of giant companies and the layoffs of thousands of workers.”

Translation: “Such occurrences are not common in Oman and is not part of our customs since Oman is a state of law and institutions, but we must stand against those who make these workers resort to such acts, because they left their countries and their families in order to obtain a livelihood, because workers rights are not a game.

Translation: “According to what I received, they are the workers of Al-Turki and Al-Tasnim Company on strike because they have not been paid their salaires for months.”

While Oman fiscally appears to be the worst off from all the GCC states, such economic instability and ‘domestic discontent’ is not alien to the rest of the Gulf. Similar sporadic protests and have occured in Kuwait over repatriation and salaries; in Saudi Arabia again over repatriation; and in Qatar over unpaid wages of expatriate workers.

Status of Covid-19 in the Gulf

Thanks to the diligent work of Brian Whitaker on Al-Bab.com it is possible to review Covid-19 cases in the Middle East as a whole. With many GCC states lifting lock down and easing restrictions on public movement there are fears of a larger second wave of cases. In Saudi Arabia and Qatar these fears are now being voiced following the easing of restrictions, but they are becoming a serious prospect for Oman which has recently experienced a steady increase in cases. On top of this the proportion of cases has shifted from being majority migrant workers to majority Omani citizens.

What exactly will happen with the pandemic can not be predicted, but certain things remain certain. All the economic consequences that await Gulf countries in 2020 are going to disproportionately hit the migrant worker population. As was the case in the 2008–2009 global financial crisis GCC states will insulate themselves by dismissing the most vulnerable and poorly-protected workers. If not infected with the disease they will surely undergo strenuous pressures during repatriation, all to arrive in their home countries were job prospects and healthcare protections are worse.

We have yet to see all the subsequent human loss that is to come from the pandemic’s effect across the world, but no one needs clairvoyance to see the suffering migrant workers are, and — will be — subjected to.